Spotlight On: Urogynecology/Vaginal Surgery

This month we cast a spotlight on articles, SurgeryU videos, and Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology (JMIG) article recommendations from the AAGL Urogynecology/Vaginal Surgery Special Interest Group (SIG) led by Chair, Lisa Hickman, MD.

This month we cast a spotlight on articles, SurgeryU videos, and Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology (JMIG) article recommendations from the AAGL Urogynecology/Vaginal Surgery Special Interest Group (SIG) led by Chair, Lisa Hickman, MD.

Access to SurgeryU and JMIG are two of the many benefits included in AAGL membership. The SurgeryU library features high-definition surgical videos by experts from around the world. JMIG presents cutting-edge, peer-reviewed research, clinical opinions, and case report articles by the brightest minds in gynecologic surgery.

SurgeryU video recommendations by our SIGs are available for public access for a limited time. The links to JMIG article recommendations are accessible by AAGL members only. For full access to SurgeryU, JMIG, CME programming, and member-only discounts on meetings, join AAGL today!

SIG Recommended SurgeryU Video #1:

Laparoscopic Excision of Persistent Midurethral Sling Erosion – SurgeryU by AAGL

Peter L Rosenblatt MD, and Nabila Noor, MD

This video highlights the excision of a mesh erosion into the bladder for a patient who presented with pelvic pain and hematuria. While a rare complication, this video by Dr. Rosenblatt demonstrates anatomic considerations and excellent surgical techniques. Dr. Rosenblatt is known for his extensive surgical skillset and is a leader in urogynecology and reconstructive pelvic surgery

SIG Recommended SurgeryU Video #2:

Laparoscopic and Robotics Sacrocolpopexy, The Ins and Outs

Patrick J. Culligan, MD, FACOG, FACS

This excellent video by Dr. Culligan highlights patient selection, anatomic considerations, and surgical tips and tricks. A fantastic, high-yield overview of sacrocolpopexy from an expert in urogynecology and reconstructive pelvic surgery.

JMIG Article Recommendation #1:

Long-Term Costs of Minimally Invasive Sacral Colpopexy Compared to Native Tissue Vaginal Repair With Concomitant Hysterectomy

Jonathan P. Shepherd, MD, Catherine A. Matthews, MD and Lauren A. Cadish, MD

In this modeling study performed at a tertiary medical center, patients undergoing total vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension (vaginal native tissue repair) were compared to those undergoing minimally invasive total hysterectomy with sacrocolpopexy were compared to determine long-term costs of these procedures. This study found that minimally invasive total hysterectomy with sacrcolpopexy was more costly than a vaginal native tissue repair, by nearly $4,500, but that nearly 15% more women with a vaginal native tissue repair will have recurrent prolapse for which they will not choose to undergo recurrent prolapse repairs. Interestingly, the authors found that nearly seven women would have to undergo a minimally invasive hysterectomy with sacrcolpopexy to prevent one woman having prolapse recurrence after vaginal native tissue repair. This study supports vaginal native tissue repair as a more cost-effective strategy for the index surgical approach for uterovaginal prolapse.

JMIG Article Recommendation #2:

Sarah E. Bradley, MD, Sarah A. Ward, MD, Karen A. Schirm, MD, Bayley Clarke, MD, Robert E. Gutman, MD, and Andrew I. Sokol, MD

In this single-center, retrospective cohort-study, the authors provide one-year data on outcomes and complications for three different approaches to laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy: Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy at the time of total vaginal hysterectomy with vaginal mesh attachment, laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy for individuals with post-hysterectomy prolapse and laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy at the time of supracervical hysterectomy. This study included 650 patients who were primarily white, non-smokers, post-menopausal and with stage 3 prolapse. The authors found no difference in composite failure rates (symptomatic prolapse, objective prolapse on exam, and retreatment) or mesh complications between the groups. This well-done, large cohort adds to the evidence supporting the short-term safety and efficacy of vaginal hysterectomy with vaginal mesh attachment at the time of minimally invasive sacrocolpopexy compared to more commonly utilized approaches and enables surgeons to take a patient-centered approach when to surgical planning. Additional intermediate and long-term outcomes data is needed.

SurgeryU Video and JMIG Article Recommendations By:

Lisa C. Hickman, MD, FACOG, FACS

Dr. Hickman is Chair of the AAGL Urogynecology & Vaginal Surgery Special Interest Group and Associate Professor of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Division of Urogynecology & Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery, at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus, Ohio.

MESSAGE FROM THE SIG CHAIR

The Urogynecology/Vaginal Surgery SIG is focusing this month on the use of mesh for the treatment of prolapse and stress urinary incontinence. Our upcoming webinar on August 28, 2025, at 5:00pm PDT, is entitled “When Mesh Goes Wrong: Surgical Management of Complex Cases and Important Perioperative Considerations.” We encourage you to attend! This topic was selected given the prevalent mesh use in gynecologic surgery and the possibility that caring for women with a history of mesh, including its complications, will affect the practice of gynecologic specialists and subspecialists alike.

A key aspect of the pathophysiology of pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence is the compromise in pelvic supports. While non-surgical as well as non-mesh options are frequently implemented to treat these common conditions, synthetic mesh implants have been the mainstay of prolapse and stress urinary incontinence treatments. Biologic grafts have also been an appealing option, but one that has never reached widespread implementation. Graft augmentation for the surgical management of these conditions is utilized to improve the repair durability, thereby overcoming the inherent weakness in the native tissue.

Since the 1970’s, hernia mesh was fashioned by surgeons to repair pelvic organ prolapse via sacrocolpopexy, as no FDA-approved products were available at that time. Similarly, surgeons modified the same materials to create slings for stress urinary incontinence treatment, until the first mesh product was FDA-approved in 1996 for this indication. Soon after, the first commercially available mesh kit, the tension-free vaginal tape (TVT, Ethicon), was introduced in 1998. And by 2002, the first FDA-approved transvaginal mesh kit for prolapse came to the market. The use of mesh in clinical practice increased significantly, such that by 2010 over a third of prolapse repairs utilized transvaginal or sacrocolpopexy mesh. Interestingly, the use of biologic materials predated the use of synthetic meshes for prolapse and incontinence, with reports as far back as the early 1900’s where autologous muscle flaps were used to treat stress incontinence.

There continues to be a search for the ideal graft material to augment prolapse and stress urinary incontinence repairs. For synthetic mesh, there are a variety of properties important for maximizing its structural integrity while minimizing the risk of complications. Today, the mesh products used for prolapse and stress incontinence are made from polypropylene, and are monofilament, macroporous, knit, low-stiffness, and lightweight. These properties help reduce the likelihood of bacterial seeding, minimize the inflammatory host-response to a foreign body implant and promote tissue in-growth. Still, complications such as mesh exposure/erosion, pain and dyspareunia, and inflammatory responses continue to be a challenge. Indeed, complications such as these prompted the FDA to halt the manufacturing of transvaginal mesh products in 2019. Biologic grafts, including autograft (derived from the patient), allograft (derived from a human, typically cadaveric) and xenograft (derived from an animal), minimize or negate the chance of these complications, however in head-to-head studies, biologic grafts continue to be inferior to synthetic meshes in their durability and success rates. As such, their use is often limited to specific cases.

Researchers today continue to study graft materials to develop a product that minimizes the host-response, maximizes durability, and reduces complication risk. This may involve coating meshes or capitalizing on properties inherent to biologics to more closely mimic the characteristics of vaginal tissue. While these grafts have significantly evolved since their implementation in the 20th century, we look forward to what is forthcoming in this arena so the care of women with these pelvic floor disorders can continue to be advanced.

About the Author:

Lisa C. Hickman, MD, FACOG, FACS

Dr. Hickman is Chair of the AAGL Urogynecology & Vaginal Surgery Special Interest Group and Associate Professor of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Division of Urogynecology & Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery, at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus, Ohio.

Case Report: Mesh as a Nidus for Pelvic Abscess

A 54-year-old presented to urogynecology clinic for six months of bloody vaginal discharge and a recurrent bulge to the level of the introitus. History was notable for several gynecologic surgeries including a hysterectomy in 2008, an open abdominal sacrocolpopexy with TVT sling in 2012, and a sacrospinous colpopexy with apical mesh excision in 2024. Physical exam revealed a pinpoint lesion of mesh exposure at the vaginal apex and a one-centimeter full thickness exposure of the left arm of the sling. She had stage 3 posterior predominant prolapse. A two-step approach was planned: first excise the mesh both abdominal and vaginally and then discuss another prolapse repair surgery.

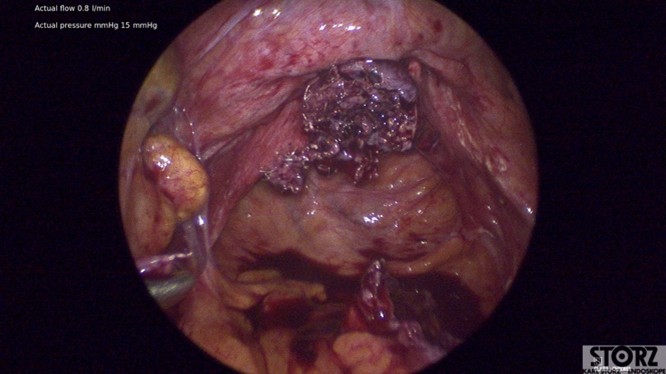

Laparoscopically, the small bowel was adherent to the apex of the vagina with overlying peritoneum from the tail of the mesh. There was severe scarring with the bowel wrapping apically. There was no ability to see the sacral promontory due to fibrotic scar and adhesions (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Figure 1

Laparoscopic mesh excision was performed by entering the peritoneal tunnel, where moderate gelatinous fluid was encountered consistent with chronic mesh exposure and colonization (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Figure 2

The apical tail of mesh was freed from the small bowel with sharp dissection, however given dense scar tissue and the proximity to the appendix, approximately 1 centimeter of mesh was left behind attached to the sacral promontory. The anterior and posterior vaginal mesh attachments were then excised using sharp dissection, leaving behind healthy vaginal tissue.

Next, a vaginal approach was used to close the cuff and excise the prior TVT. The patient was discharged home following surgery.

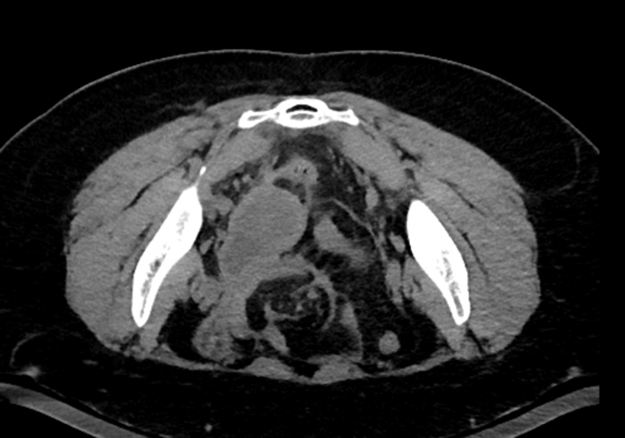

On POD#4, patient called in with bleeding from her umbilical incision without infectious symptoms, and observation was encouraged. On POD#7, malodorous discharge from her umbilical incision was noted (without fever/chills). She was referred to an urgent clinic for evaluation and was prescribed 7 days of cephalexin QID x7 days. On POD#16, given increased pain and subjective fevers/chills, she was admitted to the gynecology service. A CT scan revealed a multiloculated abscess from the right pelvic sidewall to the vaginal cuff measuring 6cm x 4cm (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Figure 3

No communication was noted between her umbilicus and the abscess. She was started on intravenous ceftriaxone and metronidazole, and underwent a trans gluteal drain placement (Figure 4). Her symptoms improved by hospital day 2, and she was discharged home with a 14-day course of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid.

Figure 4

At her 6 week post operative visit, the patient was doing well, s/p drain removal without any ongoing pain or vaginal discharge. Recurrent prolapse was noted, yet mildly symptomatic. This case presents an interesting question of how to manage patients who have undergone laparoscopic mesh excision, due to mesh exposure which has been colonized and/or infected. The mesh crosses the vaginal microbiome into the sterile peritoneal space. Can we prevent post operative pelvic abscess? No clear answer exists in the literature, but options include post operative empiric antibiotics, leaving a drain in place, or perhaps even more creative measures utilized by other specialties (antibiotic bead placement).

About the Author:

Zoe Stukenberg, MD

Audra Jolyn Hill, MD

Dr. Stukenberg is in Program Year 3, OBGYN, at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Utah. Dr. Hill is Associate Professor in the Division of Urogynecology at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Utah.

Mesh in 2025: Revisiting Vaginal Mesh

“Vaginal Mesh” for prolapse remains a charged phrase in the United States and worldwide, yet evidence continues to mature. In April 2019, the FDA ordered manufacturers to stop selling transvaginal mesh kits for pelvic organ prolapse in the U.S., post-market surveillance of these devices continues. Importantly, that decision does not apply to mesh used for stress incontinence or to mesh placed abdominally for sacrocolpopexy (SCP). As a result, contemporary U.S. prolapse “mesh use” is largely synonymous with abdominal/ minimally invasive SCP. Two recent NIH Pelvic Floor Disorders Network trials, SUPeR and ASPIRe, provide more insight about where trans-vaginal mesh belongs (and doesn’t) in 2025.

SUPeR: uterine-sparing mesh hysteropexy vs hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension (Nager et al)

In the original 3-year results, sacrospinous mesh hysteropexy showed no statistically significant difference in composite failure versus vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral suspension (USLS). Hysteropexy demonstrated shorter operative time and an 8% mesh exposure rate. However, 5-year follow-up showed a significant difference between the groups; mesh hysteropexy had lower composite failure than hysterectomy with USLS (adjusted HR 0.58; 95% CI 0.36–0.94), while patient-reported outcomes were similar between groups. Interpreted clinically, SUPeR suggests that a well-executed uterine-sparing mesh hysteropexy can be as durable—and possibly more—than native-tissue hysterectomy repairs. Mesh exposures were 8% for the hysteropexy group, while granulation and suture exposures were 12% and 21% respectively for the hysterectomy group. Patient experience with these three postoperative adverse events may not differ significantly and may have similar levels of impact and bother.

ASPIRe: three-arm comparison for apical vaginal vault prolapse (Menafee et al).

Post-hysterectomy patients were randomized to native-tissue vaginal apical repair, transvaginal mesh (TVM), or abdominal SCP. At 36 months, adjusted failure incidence as measured by a composite outcome of objective and subjective measures was 28% for SCP, 29% for TVM, and 43% for vaginal native tissue. While all three treatments showed sustained improvement in patient reported outcomes, using the primary composite failure outcome, SCP was superior to native tissue. Interestingly, TVM was noninferior to SCP and not statistically superior to native tissue after multiplicity adjustment. Mesh exposure rates were low (3% SCP; 5% TVM) and dyspareunia uncommon across arms. In other words: both mesh-augmented strategies outperformed native tissue though only SCP showed a statistical difference, and low complication rates, including mesh exposure demonstrate the safety of all approaches.

How does this inform practice?

- SCP remains the U.S. workhorse for apical support when mesh is acceptable to the patient: it offers durable anatomic outcomes with overall low exposure rates and is widely regarded as the “gold-standard” apical repair in contemporary reviews.

- Transvaginal mesh for POP is not commercially available in the U.S. While current FDA policy and product availability preclude routine clinical use for transvaginal mesh, study data continues to support the efficacy and safety of transvaginal mesh in expert hands.

- Native-tissue repairs remain essential. For many patients native-tissue apical suspensions remain an excellent option with good patient reported outcomes though may not be quite as durable as mesh augmented repairs.

Looking ahead. These two NIH trials raise the question for rigorously selected patients and expert surgeons: Should transvaginal mesh be a viable option? The high success rates and overall low adverse event rates in these two trials would suggest yes. For now, however, transvaginal mesh remains purely experimental as it may be an uphill battle bringing products back to market given the current regulatory atmosphere and public opinion.

References

- Nager CW, Visco AG, Richter HE, Rardin CR, Komesu Y, Harvie HS, Zyczynski HM, Paraiso MFR, Mazloomdoost D, Sridhar A, Thomas S; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Effect of sacrospinous hysteropexy with graft vs vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension on treatment failure in women with uterovaginal prolapse: 5-year results of a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021 Aug;225(2):153.e1-153.e31. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.03.012. Epub 2021 Mar 12. PMID: 33716071; PMCID: PMC8328912.

- Menefee SA, Richter HE, Myers D, Moalli P, Weidner AC, Harvie HS, Rahn DD, Meriwether KV, Paraiso MFR, Whitworth R, Mazloomdoost D, Thomas S; NICHD Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Apical Suspension Repair for Vaginal Vault Prolapse: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg. 2024 Aug 1;159(8):845-855. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2024.1206. Erratum in: JAMA Surg. 2024 Aug 1;159(8):960. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2024.2789. PMID: 38776067; PMCID: PMC11112501.

About the Author:

Kate L. Woodburn, MD

Dr. Woodburn is Assistant Professor of Urology and Obstetrics and Gynecology at Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist in Winston-Salem, North Carolina.